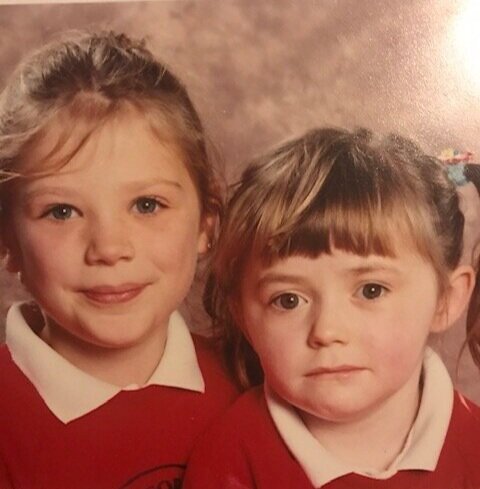

My little sister Lucy died aged 26 after a short and sudden collapse in January 2021. Lucy had, the most incredible, zest for life. She faced a lot of challenges in her short life, yet she was remarkably grateful and uncomplaining. She was a talented composer who touched many people with her music. She was also a politically savvy, passionate advocate for disability and disabled rights. She was witty and intimidatingly clever. I will never forget when (as an A* GCSE history student myself) my then teacher told me Lucy was the most truly intellectual and promising history student she’d ever had. Lucy was also kind, and loyal and funny and gentle. She made a lot of her (too few) years and I miss her every day.

1. Lucy was exceptional. In a lot of ways. When she was first diagnosed with the disability that would, in some ways, shape her life, my parents were told they had ‘more chance of winning the lottery’ then a having a child with her condition. Lucy never let her disability define her. I won’t say she rose above it because she didn’t. It was part of her, a proud part of her. But it wasn’t all of her. She lived with, and often embraced it, but it also signified a huge amount of loss for her.

2. Living with Lucy, and her talent and condition, could be challenging. Although I’m sure that she would have said the same about me. Lucy had this incredible imagination and a way of drawing people into her world. Finding herself in music Lucy became a composer. When she died there was an outpouring in the classical music world that was, at once, comforting and overwhelming. To know she’d reached so many people in the corner of the world she had made her own was touching. At the same time the intense sense of loss, about her as a person but also her potential, about the future she no longer had, was difficult. The occasional sense of her as a small piece of public property, to be mourned by people en masse, could be be challenging. Outpourings of grief (however small) are not without their downsides to those closest to the person behind them.

3. Time moves very slowly when you’re grieving. Except that it doesn’t, not really. It moves at the exact same pace as before, but you stay stuck. People forget, and they move on. They stop checking in and they forget that, for you, the loss is as real as it was six months ago. The world carries on spinning but you stay, one foot dragging you into the future (your future) and one rooting you to the past. To before your person was gone.

4. Everyone is different but, for me, people either expect you to want to talk about how you feel, or, don’t want to talk about death at all. And in reality you just want to be able to talk about your person. You want to be able to talk about your sibling like anyone with a living one does. For me, I knew how I felt. I didn’t need therapy or support to accept what happened. Lucy died and I have this unimaginable hole in my life that makes me sad all the time. I don’t need to talk about that because I know it and live it and, ultimately, I have my ways of coping with it. I miss being able to tell people about her without second guessing myself though. I miss being able to mention her without fearing I will make the conversation awkward.

5. The small things can be the hardest. The things that remind you of your loss. The friends you’ve known your whole life, the ones who still have their siblings. Your child who asks questions about death in such a blasé and, sometimes unrelenting, way. The realisation that actually you’re scared of dying. The realisation that your best hope is the massive hole in your life gets smaller, more manageable. The need to protect others who may be hurting more than you, for me as a sibling, notably my parents. The things that make you human, caring about others, loving, feel more intense after a loss. And then the realisation that, yes this is a near universal human experience, loving and losing. An unavoidable part of life.